Prisoner Capt. Jonathan Walker in the pillory having his face smashed, before be branded by a Florida Federal Judge!

Jonathan Walker (was born on Cape Cod in Harwich) was a Florida resident (who later) moved (back) to Massachusetts to separate himself from the institution of slavery. He returned to Florida three years later and attempted to help seven slaves, formerly in his employ, to escape. He was captured and tried in the Superior Court of Escambia County, in the District of West Florida, Territory of Florida. On being convicted, he was pilloried, pelted with rotten eggs, imprisoned for eleven months, fined, and branded on the hand branded by a U. S. Marshal with the letters “S.S.” which stood for “slave stealer.” This episode was the inspiration for John Greenleaf Whittier’s abolitionist poem, The Branded Hand.

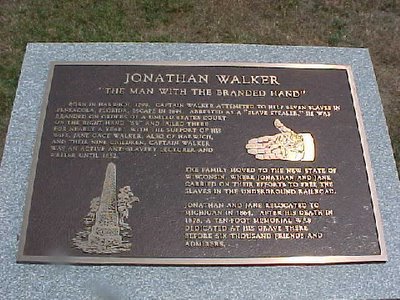

This is a picture taken by Harwich High School's, History Chair, Richard Houston, The Capt. Jonathan Walker plaque is locate in front of Brooks Academy next to the powder house, and outhouse on the curve of Rtes, 124 & 39, directly in front on the Harwich Congregational Church.

This is a picture taken by Harwich High School's, History Chair, Richard Houston, The Capt. Jonathan Walker plaque is locate in front of Brooks Academy next to the powder house, and outhouse on the curve of Rtes, 124 & 39, directly in front on the Harwich Congregational Church. Here is the author's photo. John L. Hoh, the great, great, great newphew to Jonathan Walker who lives in Wisconsin.

Here is the author's photo. John L. Hoh, the great, great, great newphew to Jonathan Walker who lives in Wisconsin.Underground Railroad

By John L. Hoh, Jr.

Suite 101

When we talk about the Underground Railroad, we often think of the northerly migration of American slaves into Canada. Northern states weren’t always safe havens given that bounty hunters had the protection of the federal government to capture runaway slaves. Canada, being a territory of the United Kingdom, had outlawed slavery.

But along the southern coasts slaves used a seaway Underground Railroad. Here again a British territory was the destination, usually the Bahamas. And it was just such an attempted escape that has captured my attention to the Underground Railroad. This escape attempt included an ancestor of mine.

Meet my great-great-great uncle, Captain Jonathan Walker.

To be sure, this is “shirt-tail” relativity. My grandfather’s sister married Captain Walker’s grandson, Lloyd Garrison Walker, Jr. And if that name sounds familiar, it’s because Jonathan and Jane Walker named their children after leading abolitionists of the day: John Bunyan Walker, Altamera Walker, Nancy Child Walker, Sophia Walker, Mary Gage Walker, the twins Maria and Lloyd Garrison Walker, William Wilberforce Walker (the original WWW?), and George Fox Walker.

Walker had come to a realization that something was very much wrong with slavery. He worked with Africans that did the same work for far less pay. He was nursed back to health by strangers who had dark skin. He saw the evils of slavery in the fields. When he became convinced to take an active role in the activity of the abolition of slavery is hard to pinpoint. His notes indicate an epiphany sometime during the attempted journey to the Bahamas! Starting out on the journey, Walker considered the activity one of honoring a request of a friend and not necessarily a blow against slavery.

Born and raised in Harwich, Massachusetts, Jonathan Walker grew up in an area that was against slavery. John Adams, a leading delegate to the Continental Congress in 1776, desired slavery outlawed in the new nation and spelled out in the Declaration. Politics being what it is, and the vote making any resolution of revolution unanimous to pass, slavery was upheld to keep the thirteen colonies united for independence. The Constitution spelled out that slavery was the decision of states—and took an amendment to abolish slavery once and for all. (Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation only applied to southern states in rebellion and they had to be conquered to put the document in force; southern border slave states were not affected by the Emancipation.)

Walker became a sailor and ultimately owned his own boat (hence the title “Captain”). He soon set up residence in Pensacola, Florida. Florida at that time was a territory, not yet a state. Whether he aided slaves in escaping before his infamous journey is never known. It was alleged by others, but no mention is ever found in Walker’s writings. Walker biographer Alvin Oickle believes Walker was not active in the Underground Railroad before 1844. Walker was known in Pensacola to be a man who considered African-Americans his equal. He often employed them and was known to be a fair man. That Walker would be approached for freedom would only be natural.

In 1844 Walker again settled in Pensacola after some time with his family in Massachusetts and a brief stay in Alabama. Walker sought to raise a sunken boat and recover the copper on it. Soon after returning, Walker writes, “I had an interview with three or four persons that were disposed to leave the place. I gave them to understand that if they chose to go to the Bahama Islands in my boat, I would share the risk with them.” Walker agreed and the date and time was set. Walker set about making plans for the trip mostly along Florida’s coast and taking two weeks time. Once they attained Cape Florida, the Bahamas was a half day’s journey. These preparations would include stowing food and water for four or five men. While stops would still need to be made for fresh food and water, the fewer stops needed the better to avoid detection on land and reach the goal sooner. This aspect would come into play when seven slaves showed up for the journey. More stops were needed and, perhaps, valuable time was lost. Had the group arrived in Cape Florida a day sooner, they may have made it to the Bahamas.

The seven who attempted this escape were three brothers, Charles, Phillip, and Leonard Johnson (claimed by George Willis); Moses Johnson and Harry and Silas Scott (claimed by Navy Lt. Commander Caldwell; and Anthony Catlett (claimed by Byrd C. Willis).

On 20 June 1844, Walker set out with his boat, ostensibly to find the wreck he was trying to recover. On 22 June his boat was seen again in the bay. That night the slaves disappeared and the boat was gone in the morning. By 26 June 1844 the group arrived at St. Andre’s harbor east of Pensacola. Unknown to Walker, a false alarm had been raised about a boat west of Pensacola, near Perdido Bay. This would sufficiently divert attention away for a period of time.

But all was not well. Twice as many slaves sought to flee, meaning more stops for food and water. Each stop was fraught with peril as the group could be spotted and reported to authorities. Also, Walker appears to have become a victim of sunstroke and being exposed to the elements day and night wasn’t helping his health. He took home-made emetics to relieve his stomach pain. As the trip wore on, and Walker’s health declined, the pace of the journey slowed. Had things gone better, the escape could have been successful.

Back in Pensacola the furious slave owners were appealing to the federal government. Since Florida was a territory and not a state (statehood would come in 1845), federal marshals had jurisdiction. A letter was sent to President James Tyler, a Whig and a Tennessee slave owner. Tyler became president when William Henry Harrison died one month into office and Tyler’s term was seen as illegitimate. The Whigs, nevertheless, had just nominated Tyler as their candidate in 1844 and before the campaign began he went to New York to marry Julia Gardner. Agent Joseph Quigles, acting on behalf of the slave owners, sent this letter on 28 June 1844. On 29 June Quigles followed up with a letter to John C. Calhoun, who had been appointed Secretary of State the previous April. Some see this second letter as an indication that many did not accord the Tyler presidency any legitimacy. It could well be that Quigles was covering all bases, or he knew Tyler would be honeymooning and not around to conduct this business in a timely fashion, or Quigles wanted the secretary to begin negotiations should Walker and his group leave US territorial waters. Wanted PosterNevertheless, federal aid was requested and “Wanted” posters were sent out.

On 27 June 1844 Walker piloted the boat up St. Joseph’s Bay. He intended to haul the craft over land to St. George’s Sound and thus avoid going around Cape St. Blass. It soon became apparent that the distance was too great. The group went around the Cape on the 28th and 29th of June. Today these places are known as Port St. Joe and Cape San Blas. The group Today these places are known as Port St. Joe and Cape San Blas. The group had a 4close encounter with another boat that appeared to approach them. But the other craft changed course and never approached Walker’s group.

Thirty miles east the group reached the eastern end of Florida’s panhandle and started the southerly course to the keys and Florida’s tip. By 1 July 1844 the group reached Cedar Key (parallel to today’s city of Ocala). The trip would become tediously slow as Walker’s health deteriorated. Walker became delirious and could no longer direct the escape flight. Considering the seven slaves may have never sailed and likely knew little about Florida’s geography, progress would take much smaller steps. Walker wrote about that day: “I was somewhat delirious. I remember looking at the red horizon in the West, soon after sundown, as I thought for the last time in this world, not expecting to behold that glorious luminary shedding its scorching rays on me more.”

At this time Walker also wrote: “Among other things, my mind was occupied on [the subject of slavery] also, and I calmly and deliberately thought it over; and…came to the conclusion that slavery was evil…and therefore calculated to secure the approbation of that great ‘Judge of all the earth, who doeth right,’ and before whose presence whose presence I soon expected to appear.”

Three days later the group celebrated Independence Day only thirty miles south of Cedar Key, no doubt wondering at the irony of independence in a nation that enslaved another race. Back in Walker’s home area of Cape Cod, the Barnstable Patriot reported that the Friends of Liberty discussed the all-important subject of American slavery. They concluded that “people appear to be waking up to remove this curse from our land.”

Walker was soon returned to Pensacola after his capture. His trial would begin on 11 November 1844. But Walker needed to find legal aid—and fast.

Unfortunately, there was little sympathy in Pensacola among the legal profession. Responses to Walker’s query for legal aid went unanswered for weeks, only to be answered with righteous indignation. Walker had taken an unpopular stand in the midst of slave territory and the residents would remind him of that act.

An Abolition group in Boston attempted to secure legal aid as well. Alas, it was to no avail. Walker entered the courtroom on November 11 without the presence of a defense attorney. Walker was offered the choice of three attorneys present in the courtroom, but Walker asked for an extension, hoping that a private attorney would come through. A delay was granted to the 14th. of November. Although Walker sought a speedy trial, he also realized he would be better represented by a lawyer from Boston than by one from Pensacola. In the end Walker accepted the services of a lawyer, Benjamin Drake Wright, who had earlier spurned Walker out of indignation. Walker and Wright entered the courtroom on November 14th. to stand trial for what the state considered a crime—stealing another man’s slave. Walker, as most abolitionists at the time believed, felt he committed no crime, that no man should “own” another man.

Walker Anderson was the U.S. attorney bringing the case against Walker. Walker was charged with four counts. An interested point made by Walker biographer Alvin Oickle is that Walker was charged only with stealing four of the slaves, not all seven. Also, the slaves are not charged in the indictment. By the time Walker’s trial started, one slave had died and the remaining six were back in the custody of their “owners.”

Oickle also points out the difference in language: Walker was charged with aiding and assisting one slave’s escape, enticing another slave, and stealing a third. Oickle’s theory is that aiding and assisting was in regard to the slave who originally asked for help; stealing was in regard to slaves who simply showed up that evening and Walker could have refused passage. Another theory (mine) is that a jury could pick and choose which charge they would find Walker guilty of. The jury could find Walker guilty of a lesser crime or of a greater crime. And if the trial was overturned on a technicality, and Walker couldn’t by law be tried again, there would always be three more charges that could be levied against Walker.

JONATHAN WALKER

By Tom Carlson

Jonathan Walker, who was to become known as “the Man with the Branded Hand,” was born near Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in 1799. He went to sea at an early age and eventually became captain of his own ship. Walker also became a strong abolitionist. In 1835 he joined with Benjamin Lunday in colonizing fugitive slaves in Mexico. Lunday, a northern journalist, was among the first crusaders against slavery. Off and on over the next nine years Captain Walker sailed the waters of the Gulf Coast, assisting escaped slaves in a 12-ton whaleboat he built himself.

In 1844 Walker moved his family to Pensacola, Florida. In June of that year he agreed to take seven run-away slaves to the Bahamas by ship. Apparently Walker fell ill during the voyage and the ship drifted for several days until it was taken in tow by a salvage sloop.

Walker was put ashore at Key West and placed under arrest for aiding slaves to escape. Bail was set at $10,000. Unable to raise such a high bail, Walker stayed in jail in Pensacola until he was brought to trial before the Superior Court of Escambia County in November of 1844. Walker was convicted and sentenced to one hour in the public pillory, one year in prison for each of the slaves involved, a $600 fine for the lost work time of each slave, court costs, and finally a branding on the right hand with a readable double “S” signifying “Slave Stealer.”

A special branding iron had to be constructed for the unusual punishment. Several blacksmiths refused but eventually one agreed to make the proper tool. Walker was returned to the courtroom for the branding. His right hand was tied to a low rail at first, but when spectators complained they could not see the hand was made fast to a pillar above his head. U.S. Marshal Ebenezer Door held the hot iron against the base of Walker’s hand for 15 to 20 seconds. According to those present the branding made sizzling sound.

After the punishment Walker was returned to prison. His family and friends in the north began to work for his release. Appeals were made to the governor of Florida, beseeching him to intercede on Walker’s behalf. Through negotiations the fines and prison times were reduced. In May of 1845 the amount of $600 was paid, effecting Walker’s release.

Upon his return to New England, abolitionists hailed Walker as a hero and martyr. John Greenleaf Whittier wrote a poem in 1946 titled “The Branded Hand.” The most famous stanza of that poem went:

“Then lift that manly right hand

Bold plowman of the wave

Its branded palm shall prophesy

Salvation for the slave.”

Bold plowman of the wave

Its branded palm shall prophesy

Salvation for the slave.”

Walker traveled about the country lecturing to crowds and describing the horrors of slavery. The climax of his speeches always came when he raised his right hand to reveal the brand. He proclaimed it “the seal, the coat of arms of the United States.”

When Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Walker no longer felt the need to crusade against slavery. He moved with his wife, Jane, to Muskegon, settling on a small Fruit Farm in the Lake Harbor area. According to most accounts Walker lived quietly until his death on April 30, 1878. He was buried in Evergreen Cemetery.

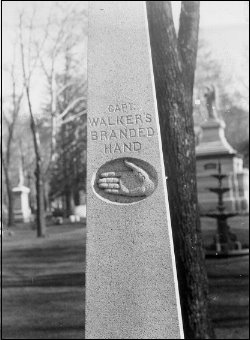

The news of Walker’s death brought tributes from all across the country, including those of William Lloyd Garrison and Fredrick Douglas. Reverend Photius Fisk, another well-known abolitionist, paid for a monument to be placed on Walker’s grave. The dedication of the monument, August 1, 1878, attracted a crowd of 6000. One side of the 10-foot obelisk contained verses of Whittier’s poem while the other side showed a carving of the branded hand.

Over the years the Walker monument has become a national shrine to those working toward racial justice. In 1956 the Urban League established the Jonathan Walker Award for those showing special commitment to that end.

In August of 1998 the granite memorial was refurbished and rededicated in a ceremony that attracted a number of descendants of Jonathan Walker. At the same time a separate monument to Jane Walker was also unveiled. The Walker grave site is located near the Irwin Street entrance of Evergreen Cemetery. Muskegon, Michigan.

In August of 1998 the granite memorial was refurbished and rededicated in a ceremony that attracted a number of descendants of Jonathan Walker. At the same time a separate monument to Jane Walker was also unveiled. The Walker grave site is located near the Irwin Street entrance of Evergreen Cemetery. Muskegon, Michigan.

No comments:

Post a Comment